Designing Ethical Behavioral Segmentation for Revolving Credit

A behavioral segmentation framework that identifies genuine revolving potential while enforcing clear ethical guardrails.

Last spring, I worked at Mastercard on a project with a financial services client to answer a deceptively simple question.

How do people actually decide to use revolving credit?

Revolving credit plays a critical role in the credit card ecosystem, yet industry testing in this area has been limited. As a result, there is no shortage of transaction data, but very little insight into the human behavior behind it. We knew what people were doing, but not why.

I approached the problem by reframing revolving credit as a decision journey. Which moments truly shape that decision? And just as importantly, which users may already be under financial strain and should not receive promotional nudges at all?

To answer these questions, I analyzed user behavior across multiple data sources to identify key inflection points in the journey.

What signals show that someone is beginning to consider taking their first step?

What subtle behavioral shifts reveal whether a user is likely to stay or begin reconsidering?

Under what conditions are former users most likely to return?

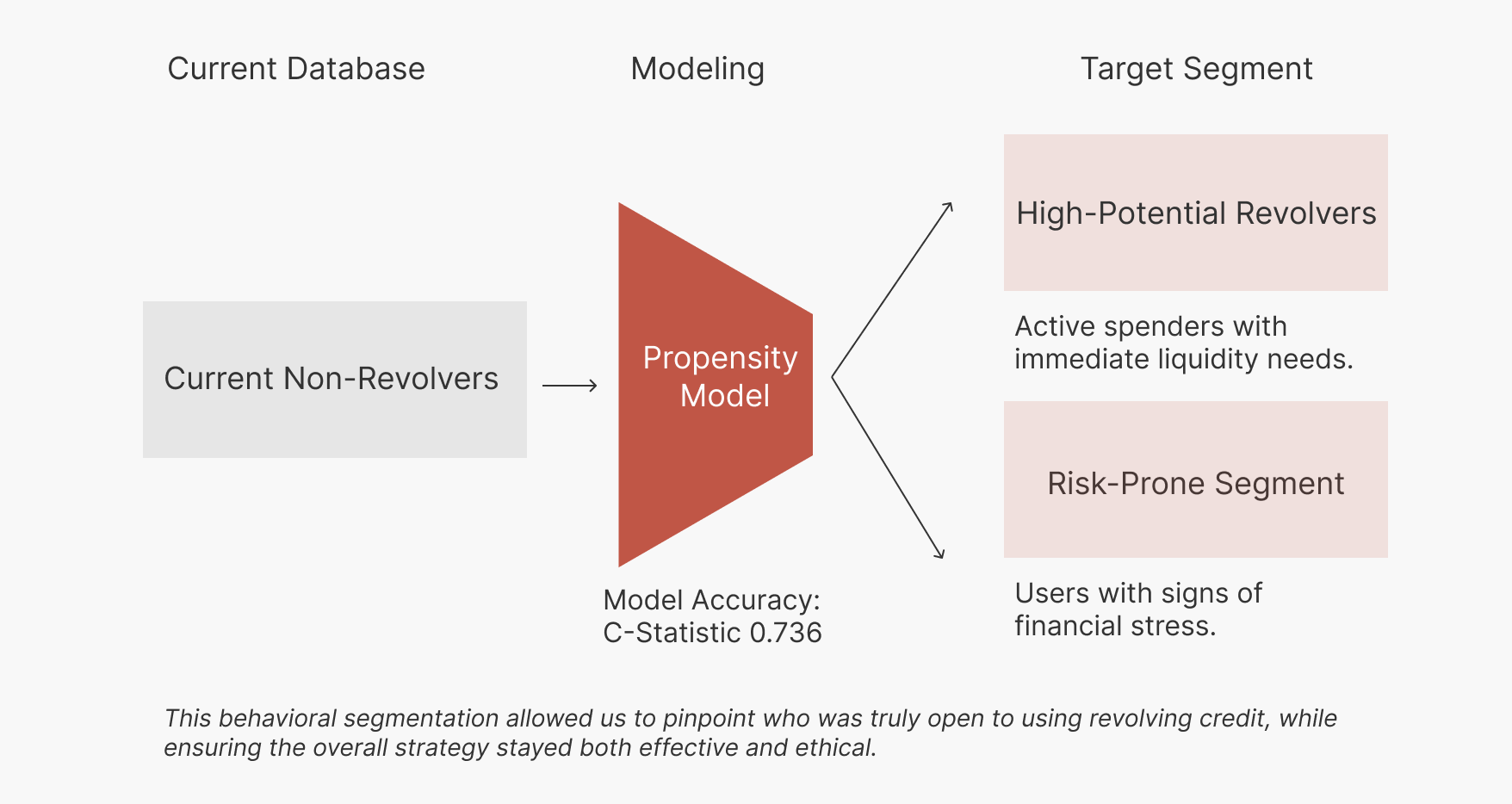

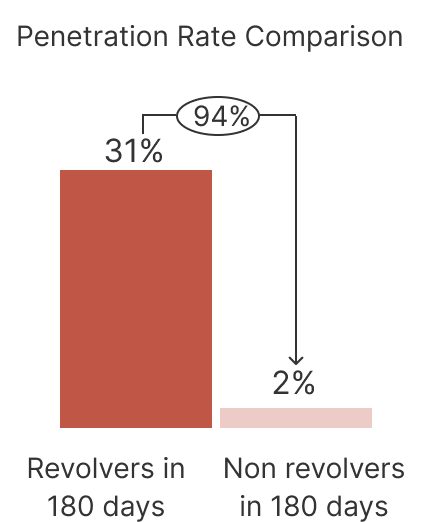

The goal of Step 1 was simple: identify people with real liquidity needs, whose behavior suggests they may turn to revolving credit in specific situations.Rather than treating all cardholders as a single group, I built a propensity model to detect behavioral signals linked to short term liquidity pressure. These signals included:

a sudden increase in overseas transactions

unusual spikes in monthly spending

frequent purchases within a short time window

Together, these readiness signals highlighted users whose spending patterns naturally align with short term borrowing needs.

By focusing on meaningful behavioral signals, Step 1 created a clear and data driven view of who might reasonably consider revolving credit and why. This allowed our outreach strategy to become more relevant, timely, and grounded in real human behavior.

After identifying the group with true revolving potential, our next step was to understand who these people actually are.

Numbers alone could tell us what they did, but not how they thought, what situations shaped their decisions, or what emotional or contextual pressures influenced their spending behaviors.

To uncover these human elements, we combined qualitative and experimental methods:

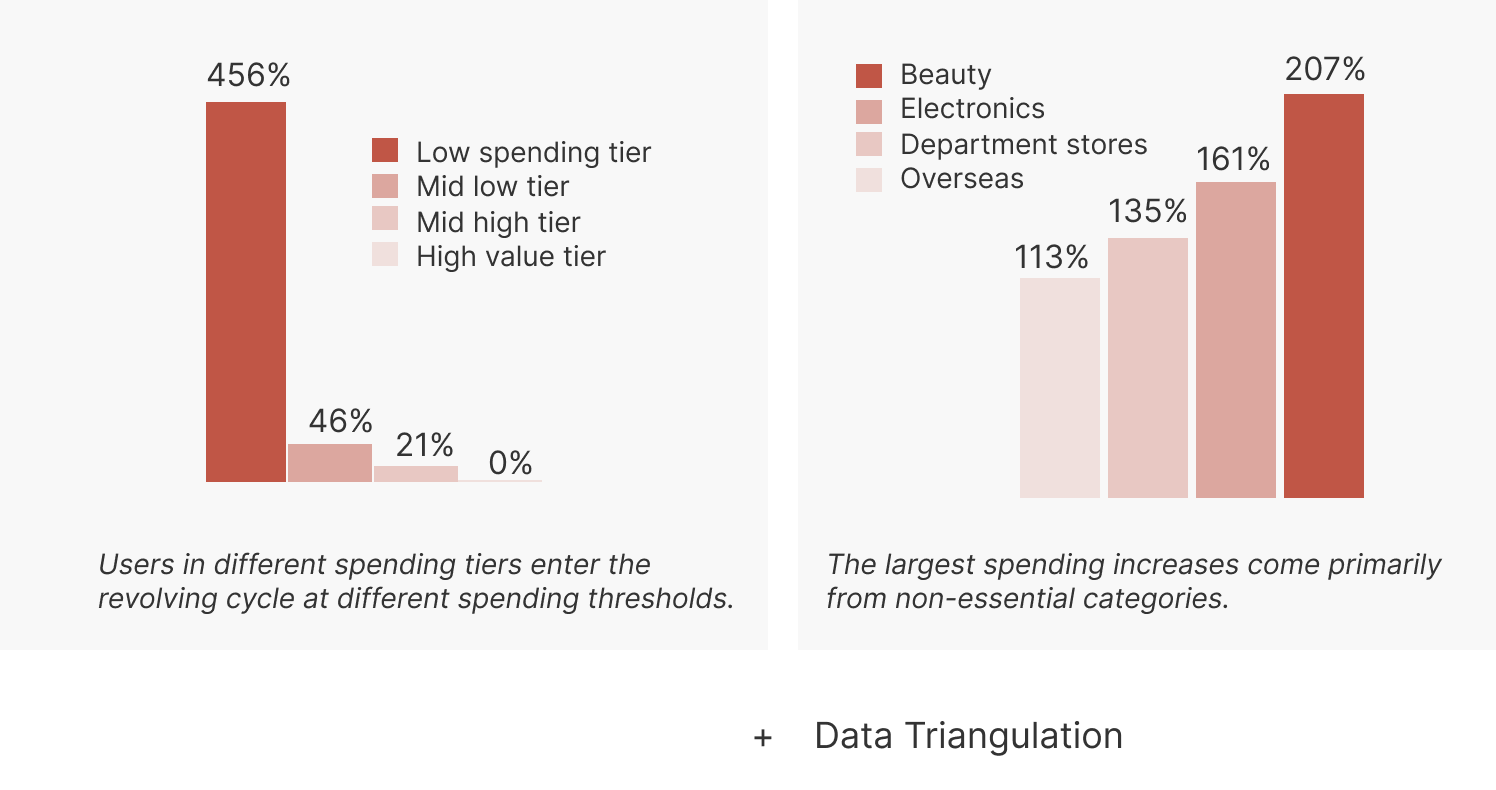

Behavioral A/B Testing: Validated hypotheses by contrasting real-world spending patterns of new vs. non-revolvers.

Qualitative Interviews: Explored mental models and situational triggers that lead to revolving.

This mixed-method approach bridged the gap between what users did and why they did it.

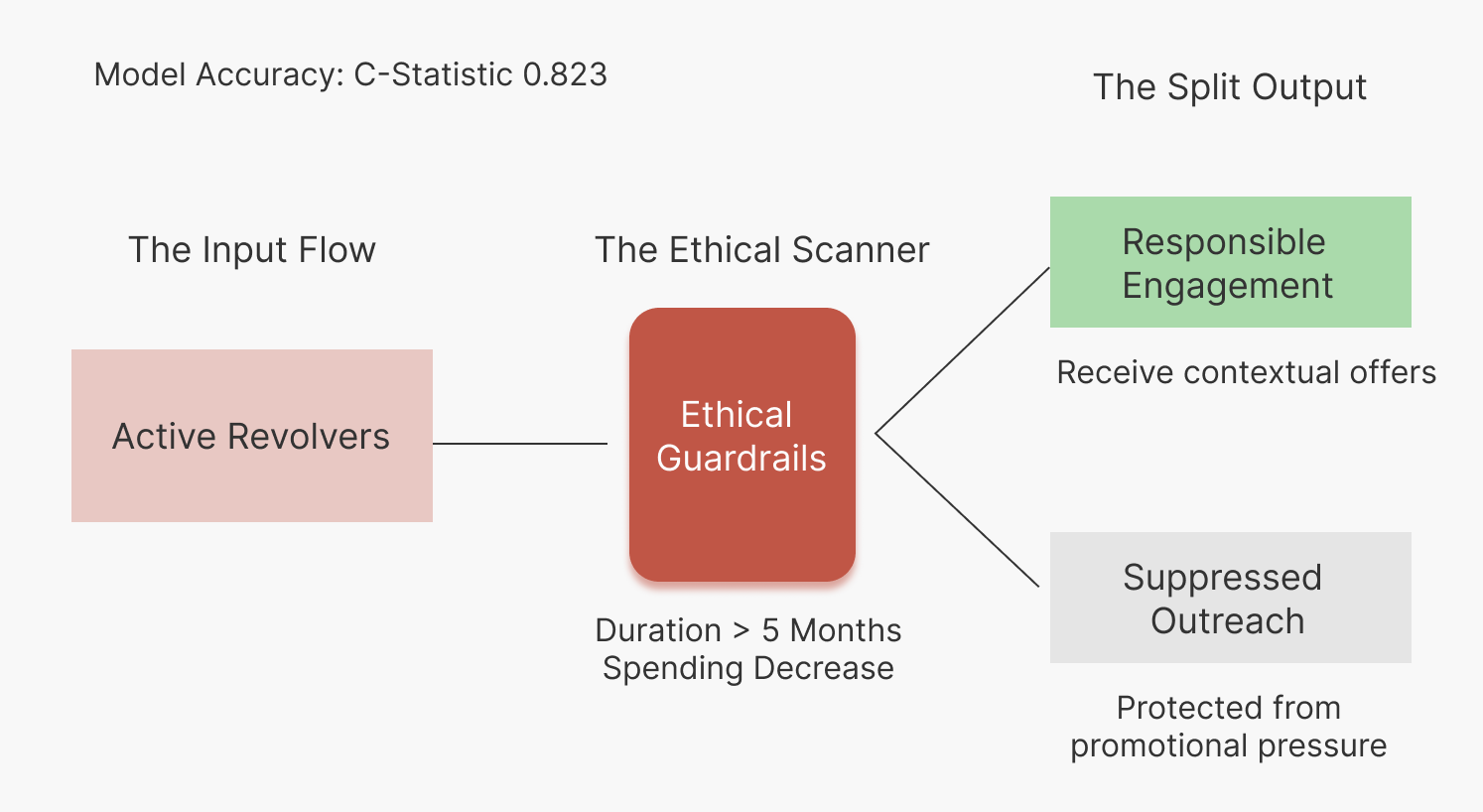

Identifying high-potential users was only half of the work.

Once customers entered the revolving cycle, we introduced a second layer of ethical guardrails to ensure our communication remained responsible.

Using multi-month behavioral data and propensity model, we filtered out users whose patterns indicated potential financial strain, such as:

staying in revolving for more than five consecutive months,

decreasing their overall discretionary spending while revolving,

or maintaining high revolving balances without recovery.

These users were intentionally excluded from promotional outreach.

Our priority was not to increase participation, but to ensure that messaging never pressured customers already experiencing financial difficulty.

This step reframed the project:

our responsibility was not only to identify opportunity—but also to protect people.

By applying these filters, we ensured that the next stage of segmentation focused only on users who showed clear repayment capacity but had temporarily increased their spending—people who were more likely experiencing short-term liquidity needs rather than long-term burden.

This process allowed us to refine our understanding of existing revolvers in a way that was not only analytically sound but also ethically grounded—protecting users who might otherwise be at risk of receiving inappropriate promotional nudges.

After excluding users who showed signs of financial strain, we focused on those with clear repayment capacity but short-term increases in spending.

At this stage, we wanted to understand two questions:

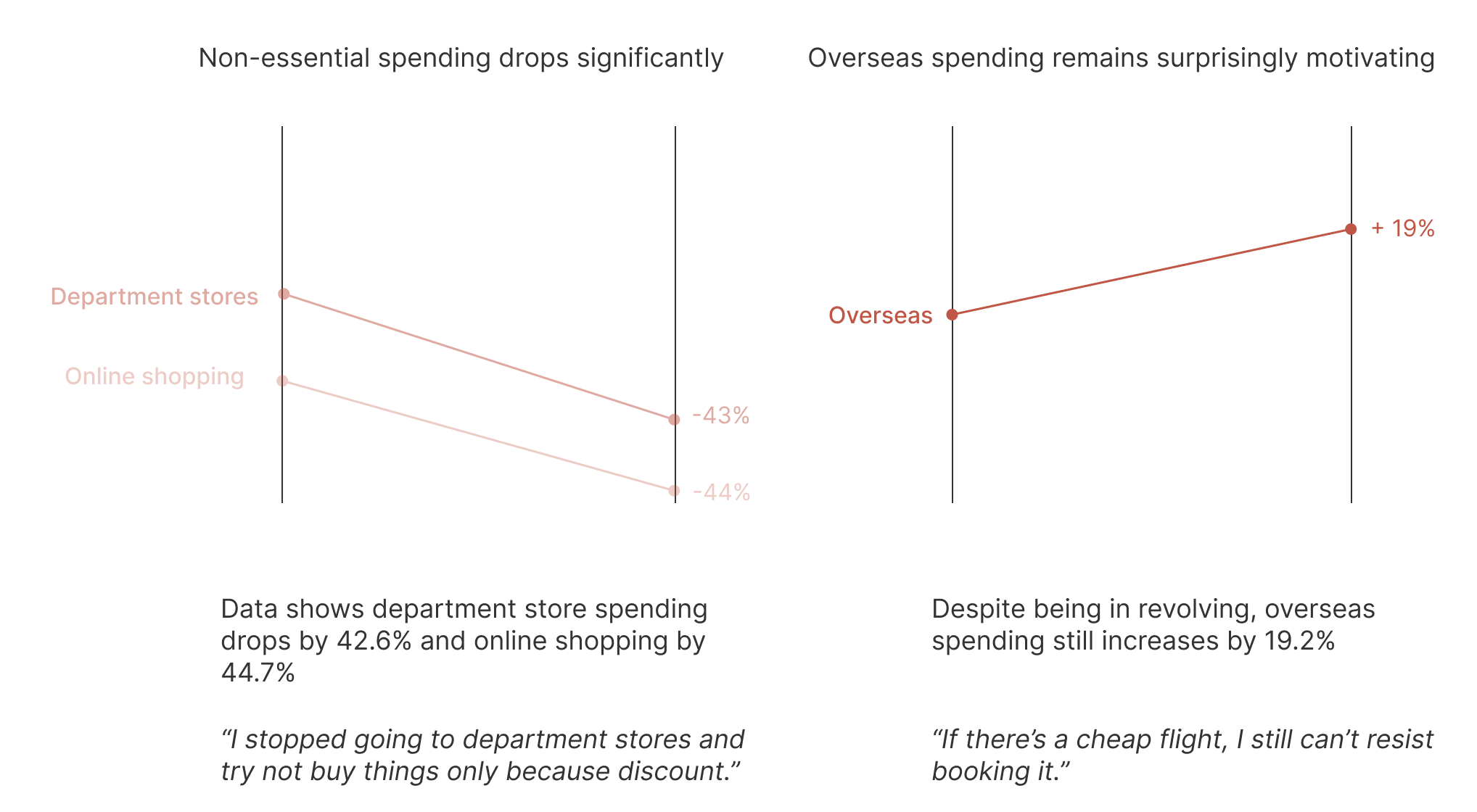

After entering revolving, what types of spending do people begin to avoid?

Despite being in revolving, which spending categories can still motivate them to spend?

To explore the psychological and situational reasons behind these shifts, we combined credit card data analysis with customer interviews.

This step revealed not just what people stopped or continued spending on, but how they reprioritize under financial pressure, and which contexts still activate spending despite heightened caution.These insights allowed us to:

Avoid pushing irrelevant or burdensome messages during periods of self-restraint

Identify moments where contextual guidance could be more helpful

Understand the emotional flexibility and constraints of revolvers’ decision-making

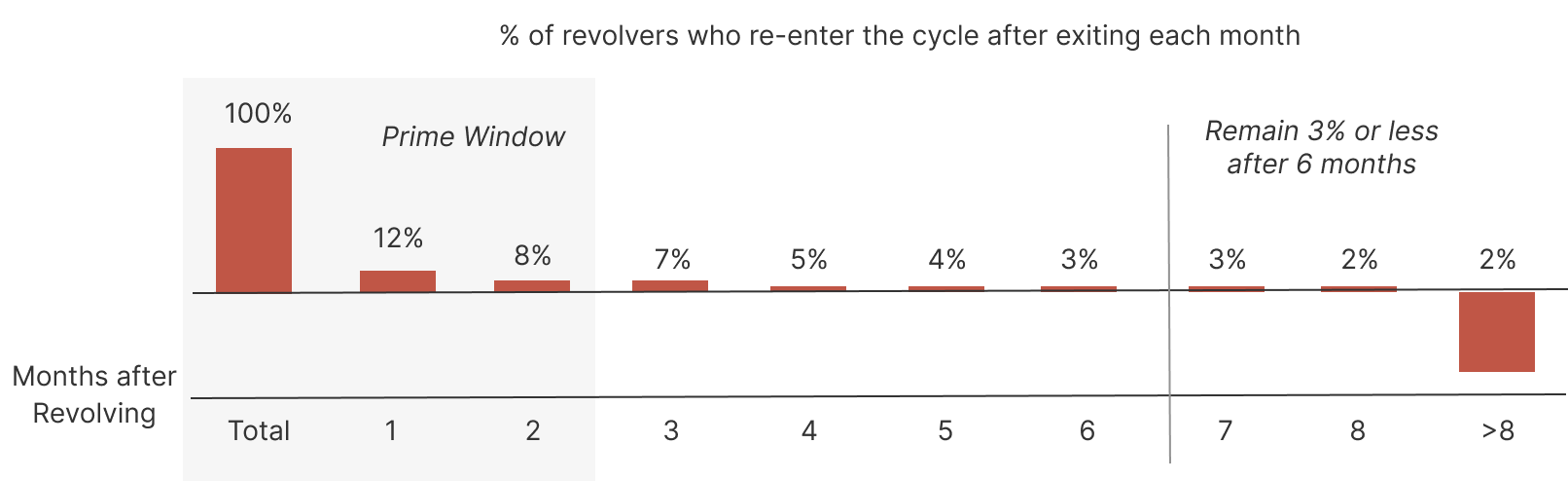

After mapping how users enter revolving, adjust their spending, and eventually exit, our final step was to understand if—and when—it is appropriate to re-engage them.

Importantly, our goal was not to push people back into revolving, but to avoid contacting users who had already regained financial stability.

When we analyzed post-exit behavior, a clear pattern appeared.

When we analyzed post-exit behavior, a clear pattern appeared.

Users who had recently left the revolving cycle were 15× more likely to return compared to non-revolvers—a momentum also reflected in interviews:

“Once you’ve carried a balance before, it doesn’t feel as hard to go back.”

But this window closes quickly. More than half of all returns happened within the first six months, after which the probability dropped to 3% or less. This suggested that timing—not incentives—is what shapes re-entry.

From this, we established a simple guiding principle:

Only users who have very recently exited—and who show no signs of financial strain—should receive light, contextual communication. For all others, especially long-term exiters, the responsible choice is to leave them undisturbed.

By aligning with users’ natural behavioral rhythms rather than pushing against them, we ensured that re-engagement remained supportive, optional, and respectful of their financial wellbeing.

This was my first time leading a full analysis as a consultant, and it taught me something simple but important: data is a way of listening to people.

Through modeling, segmentation, and A/B testing, I learned how different tools reveal different parts of a person’s needs and pressures—and how important it is to balance insight with responsibility.

Of course, the analysis had limits; our A/B test sample was small compared to the full database.

But working within those constraints helped me think more carefully and interpret results with more humility.

More than anything, this project showed me how data, when used thoughtfully, can bring us closer to understanding people—not just their behavior, but their circumstances and wellbeing.